‘Our deepest fear is not that we are inadequate. Our deepest fear is that we are powerful beyond measure. It is our light, not our darkness, that most frightens us. We ask ourselves, Who am I to be brilliant, gorgeous, talented, fabulous? Actually, who are you not to be? You are a child of God. Your playing small doesn’t serve the world. There’s nothing enlightened about shrinking so that other people won’t feel insecure around you. We are all meant to shine, as children do. As we’re liberated from our own fear, our presence automatically liberates others’. – Nelson Mandela / Marianne Williamson

When I think of inspirational quotes this is one I frequently return to because it is so direct and relatable. Mandela used it in his inaugural address and took it from an earlier source (Marianne Williamson) so it is a mishmash. The child of God reference may mean different things to people of faith or no faith, for me that doesn’t really matter. It asks an interesting question – what are we afraid of? What holds us back? At the beginning of a New Year and after nearly two years of the pandemic with all the disruption and uncertainty that brings, the world feels strangely adrift. Plenty of things to be fearful of but where does that get us?

Fear is a universal experience but it doesn’t have to be defining; it doesn’t have to set limits. Addressing what is difficult is more often liberating. I wanted to think about this in the context of community work in Thames Ward and beyond.

One of the things I am conscious of is that for community work to be successful people need to invest in something bigger than themselves. In contrast much of the social conditioning we receive encourages us to be selfish and competitive – in order to get ahead. Community work is relatively low profile relative to footballers, tech entrepreneurs, celebrities, erratic politicians – that suck up the national conversation. If the criteria for success is money, profile, status, power – and the fear of not having those things drives us, then community work is out of step with the world, playing by the wrong rules.

Here’s the thing – recent research consistently shows happiness is something we do for its own sake, not for external goals. When we become fully immersed in something we enjoy we experience what is sometimes called ‘flow’ (Csikszentmihalyi 1997). We don’t watch the clock because we are wholly absorbed and more truly ourselves. That sounds like winning to me, and along the lines of what Mandela spoke about – something liberating which spreads outwards. When I see community work in action, in its better moments, it is the same dynamic taking place.

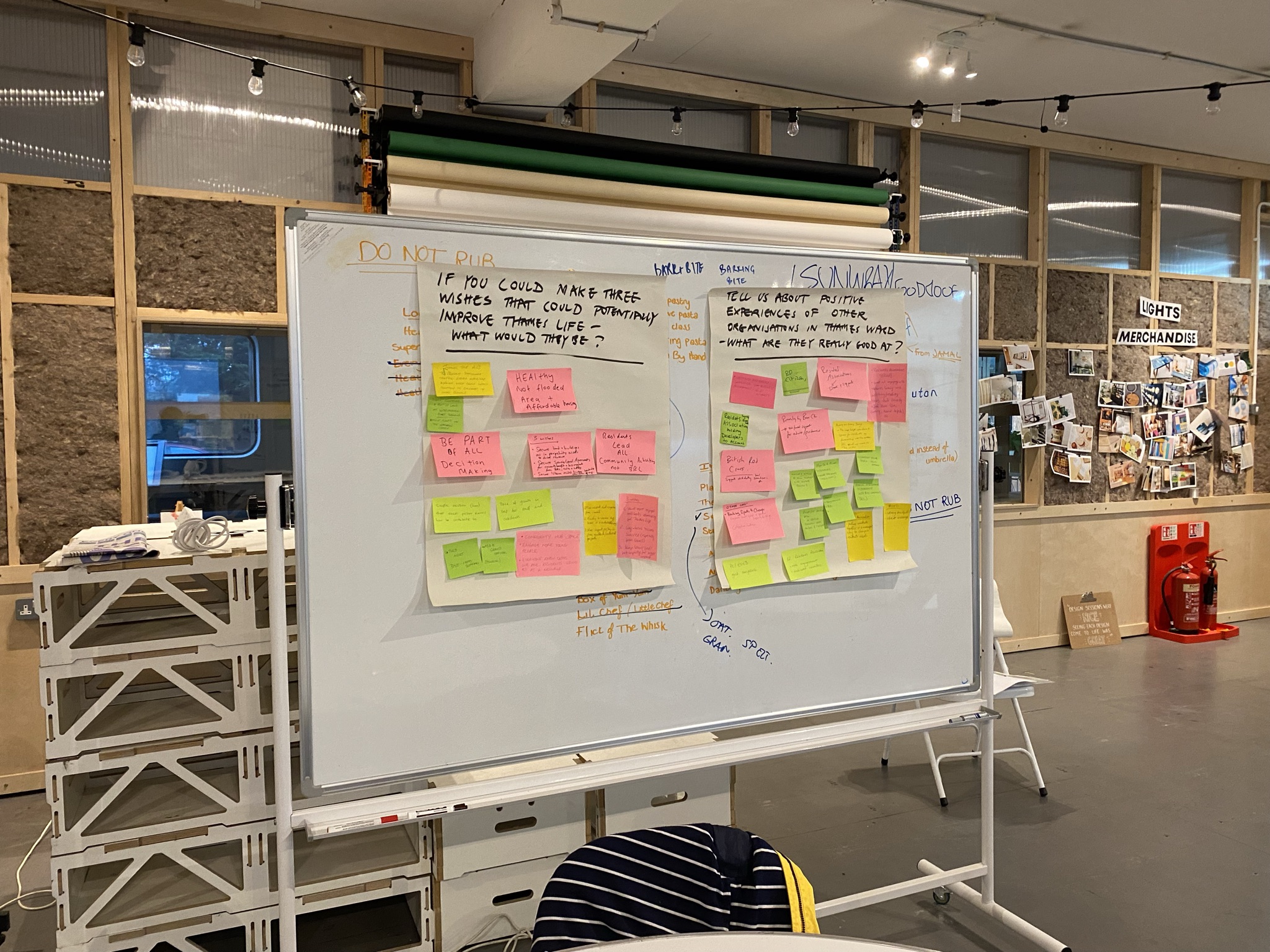

My wider reflection is that the community sector is the cornerstone of a successful neighbourhood, ward and borough. One in four people nationally regularly volunteer – that is around 17 million people across the UK. That is a good news story that deserves much more celebration. They don’t do it individually – they do it together in groups (community groups).

I hope the community sector doesn’t continue, in the words of Mandela, to ‘play it small’. Sometimes when community groups get round the table with professionals you can feel people shrinking. The resident voice if it gets any access at all rarely sets the agenda and even rarer, do they hold money and deliver services. Billions of pounds of investment come in and out of the borough in a process that is largely invisible to most people. We are a million miles from where we need to be in terms of real empowerment to leave you with another quote: ‘The first step is half the journey’ (Aristotle).

What that means is, once enough people in the community case choose not to be afraid and come to appreciate what Mandela terms, their innate brilliance and talents – that is the ‘first step’ and it changes everything. As soon as residents and community groups stop following and start leading we are more than halfway to where we need to be.